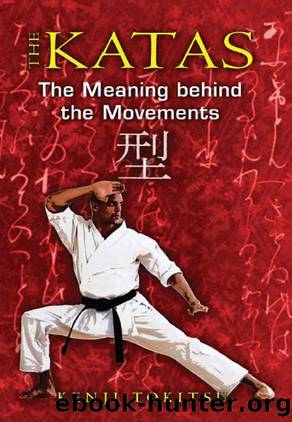

The Katas: the Meaning behind the Movements by Kenji Tokitsu

Author:Kenji Tokitsu

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Martial Arts/Eastern Philosophy

ISBN: 9781594778186

Publisher: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Published: 2011-01-26T00:00:00+00:00

ZEN AND THE WEIGHT OF WORDS

Zen is being considered here only in its practical aspect or as it relates to psychological techniques. The case of Tesshu illustrates three important points:

Zen enlightenment implies a qualitative change in the person.

This change has a tangible aspect.

This change corresponds to a reorganization of perception.

Old Japanese texts emphasize the importance of meditation in attaining a very high level in martial arts. Some master swordsmen have reached this level with the help of Zen; others reach it through the way of the sword alone, which shows that the two methods at least lead to the same result: an increase of sensorial acuity during combat.

The Zen meditation method is an amalgam of life and death. In it, all existential phenomena must be understood and experienced on the surface of death. In a sense, the perception of the world is double. In it there is a present experienced as such and a present brought into relation with death that enters into cosmic time. The precariousness of every event becomes evident when the event is moved onto a scale of time that goes from the past into the future, and as human existence is merged with nothingness. Zen meditation is meant to facilitate being placed simultaneously in a double temporality. In exploded time, consciousness, not being fixed on one point, oscillates like a wave between life and death.

Zen sayings, the kÅans, are simply a mental training process in this reorganization of time. In a kÅan, the question is concrete and understandable by the layman, and so is the response, but the relation between them is incomprehensible and devoid of meaning. Here are two sample kÅans from Toshihiko Izutsu:10

A monk asks Master Tung Shan, âWhat is the Buddha?â

Tung Shan replies, âThree pounds of flax!â

Master Pai Chang takes out a jug, puts it on the ground, and asks, âIf you donât call that a jug, what would you call it?â

The monastery abbot replies, âYou canât say that itâs a piece of wood.â

The master then turns to Wei Shan (771â853) asking for his response. In the blink of an eye, Wei Shan kicks the jug over. The master laughs and comments, âIn this contest, the abbot has been beaten by the monk.â

The replies were spoken in the presence of the objects referred to, and in this sense, they are concrete and verifiable.

The question and the reply, taken in the usual sense, cannot constitute a coherent conversation, because they surpass the logical field woven from a continuous temporal perception. They are located in a more extensive communication zone woven from the double perception of time. The reply springs from the beam of consciousness that is found between the two poles of life and death.

Seeing an absence in the presence of a thing and vice versa does not mean logically seeing that thing from two different aspects, but rather perceiving it in a double temporality. This implies as well that one is located within this perception.

The inherent difficulty with the system of words results from the impossibility of producing this combination in one narrow and continuous stroke of the pen.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8965)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8361)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7316)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7101)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6785)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6593)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5751)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5743)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5493)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5173)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4434)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4298)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4257)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4240)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4236)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4232)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4120)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3986)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3950)